** THIS IS A RE-POST From my former BLOG Site, saving here for continuity and posterity **

When one inserts the stick of challenge and change into the anthill of conventional and dogmatic thinking they are bound to stir up a commotion.

That is exactly what I thought when I read the recent Computerworld article by Eric Lai on containers as a data center technology. The article found here, outlines six reasons why containers won’t work and asks if Microsoft is listening. Personally, it was an intensely humorous article, albeit not really unexpected. My first response was "only six"? You only found six reasons why it won’t work? Internally we thought of a whole lot more than that when the concept first appeared on our drawing boards.

My Research and Engineering team is challenged with vetting technologies for applicability, efficiency, flexibility, longevity, and perhaps most importantly — fiscal viability. You see, as a business, we are not into investing in solutions that are going to have a net effect of adding cost for costs sake. Every idea is painstakingly researched, prototyped, and piloted. I can tell you one thing, the internal push-backs on the idea numbered much more than six and the biggest opponent (my team will tell you) was me!

The true value of any engineering organization is to give different ideas a chance to mature and materialize. The Research and Engineering teams were tasked with making sure this solution had solid legs, saved money, gave us the scale, and ultimately was something we felt would add significant value to our program. I can assure you the amount of math, modeling, and research that went into this effort was pretty significant. The article contends we are bringing a programmer’s approach to a mechanical engineer’s problem. I am fairly certain that my team of professional and certified engineers took some offense to that, as would Christian Belady who has conducted extensive research and metrics for the data center industry. Regardless, I think through the various keynote addresses we’ve participated in over the last few months we tried to make the point that containers are not for everyone. They are addressing a very specific requirement for properties that can afford a different operating environment. We are using them for rapid and standard deployment at a level the average IT shop does not need or tools to address.

Those who know me best know that I enjoy a good tussle and it probably has to do with growing up on the south side of Chicago. My team calls me ornery, I prefer "critical thought combatant." So I decided I would try and take on the "experts" and the points in the article myself with a small rebuttal posted here:

Challenge 1: Russian Doll Like Nesting servers on racks in containers and lead to more moreness.

Huh? This challenge has to do with the perceived challenges on the infrastructure side of the house, and complexity of managing such infrastructure in this configuration. The primary technical challenge in this part is harmonics. Harmonics can be solved in a multitude of ways, and as accurately quoted is solvable. Many manufacturers have solutions to fix harmonics issues, and I can assure you this got a pretty heavy degree of technical review. Most of these solutions are not very expensive and in some cases are included at no cost. We have several large facilities, and I would like to think we have built up quite a stable of understanding and knowledge in running these types of facilities. From a ROI perspective, we have that covered as well. The economics of cost and use in containers (depending upon application, size, etc.) can be as high as 20% over conventional data centers. These same metrics and savings have been discovered by others in the industry. The larger question is if containers are a right-fit for you. Some can answer yes, others no. After intensive research and investigation, the answer was yes for Microsoft.

Challenge 2: Containers are not as Plug and Play as they may seem.

The first real challenge in this section is about shipment of gear and that it would be a monumental task for us to determine or provide verification of functionality. We deploy tens of thousands of servers per month. As I have publicly talked about, we moved from individual servers as a base unit, to entire racks as a scale unit, to a container of racks. The process of determining functionality is incredibly simple to do. You can ask any network, Unix, or Microsoft professional on just how easy this is, but let’s just say it’s a very small step in our "container commissioning and startup" process.

The next challenge in this section is truly off base. . The expert is quoted that the "plug and play" aspect of containers is itself put in jeopardy due to the single connection to the wall for power, network, etc. One can envision a container with a long electrical extension cord. I won’t disclose some of our "secret sauce" here, but a standard 110V extension cord just won’t cut it. You would need a mighty big shoe size to trip over and unplug one of these containers. Bottom line is that connections this large require electricians for installation or uninstall. I am confident we are in no danger of falling prey to this hazard.

However, I can say that regardless of the infrastructure technology the point made about thousands of machines going dark at one time could happen. Although our facilities have been designed around our "Fail Small Design" created by my Research and Engineering group, outages can always happen. As a result, and being a software company, we have been able to build our applications in such a way where the loss of server/compute capacity never takes the application completely offline. It’s called application geo-diversity. Our applications live in and across our data center footprint. By putting redundancy in the applications, physical redundancy is not needed. This is an important point, and one that scares many "experts." Today, there is a huge need for experts who understand the interplay of electrical and mechanical systems. Folks who make a good living by driving Business Continuity and Disaster Recovery efforts at the infrastructure level. If your applications could survive whole facility outages would you invest in that kind of redundancy? If your applications were naturally geo-diversified would you need a specific DR/BCP Plan? Now not all of our properties are there yet, but you can rest assured we have achieved that across a majority of our footprint. This kind of thing is bound to make some people nervous. But fear not IT and DC warriors, these challenges are being tested and worked out in the cloud computing space, and it still has some time before it makes its way into the applications present in a traditional enterprise data center.

As a result we don’t need to put many of our applications and infrastructure on generator backup. To quote the article :

"Few data centers dare to make that choice, said Jeff Biggs, senior vice president of operations and engineering for data center operator Peak 10 Inc., despite the average North American power uptime of 99.98%. "That works out to be about 17 seconds a day," said Biggs, who oversees 12 data centers in southeastern states. "The problem is that you don’t get to pick those 17 seconds."

He is exactly right. I guess two points I would highlight here are: the industry has some interesting technologies called battery and rotary UPS’ that can easily ride through 17 seconds if required, and the larger point is, we truly do not care. Look, many industries like the financial and others have some very specific guidelines around redundancy and reliability. This drives tens of millions to hundreds of millions of extra cost per facility. The cloud approach eliminates this requirement and draws it up to the application.

Challenge 3: Containers leave you less, not more, agile.

I have to be honest; this argument is one that threw me for a loop at first. My initial thought upon reading the challenge was, "Sure, building out large raised floor areas to a very specific power density is ultimately more flexible than dropping a container in a building, where density and server performance could be interchanged at a power total consumption level." NOT! I can’t tell you how many data centers I have walked through with eight-foot, 12-foot, or greater aisles between rack rows because the power densities per rack were consuming more floor space. The fact is at the end of the day your total power consumption level is what matters. But as I read on, the actual hurdles listed had nothing to do with this aspect of the facility.

The hurdles revolved around people, opportunity cost around lost servers, and some strange notion about server refresh being tied to the price of diesel. A couple of key facts:

· We have invested in huge amounts of automation in how we run and operate. The fact is that even at 35 people across seven days a week, I believe we are still fat and we could drive this down even more. This is running thin, its running smart.

· With the proper maintenance program in place, with professionals running your facility, with a host of tools to automate much of the tasks in the facility itself, with complete ownership of both the IT and the Facilities space you can do wonders. This is not some recent magic that we cooked up in our witches’ brew; this is how we have been running for almost four years!

In my first address internally at Microsoft I put forth my own challenge to the team. In effect, I outlined how data centers were the factories of the 21st century and that like it or not we were all modern day equivalents of those who experienced the industrial revolution. Much like factories (bit factories I called them), our goal was to automate everything we do…in effect bring in the robots to continue the analogy. If the assembled team felt their value was in wrench turning they would have a limited career growth within the group, if they up-leveled themselves and put an eye towards automating the tasks their value would be compounded. In that time some people have left for precisely that reason. Deploying tens of thousands of machines per month is not sustainable to do with humans in the traditional way. Both in the front of the house (servers,network gear, etc) and the back of the house (facilities). It’s a tough message but one I won’t shy away from. I have one of the finest teams on the planet in running our facilities. It’s a fact, automation is key.

Around opportunity cost of failed machines in a container from a power perspective, there are ultimately two scenarios here. One is that the server has failed hard and is dead in the container. In that scenario, the server is not drawing power anyway and while the container itself may be drawing less power than it could, there is not necessarily an "efficiency" hit. The other scenario is that the machine dies in some half-state or loses a drive or similar component. In this scenario you may be drawing energy that is not producing "work". That’s a far more serious problem as we think about overall work efficiency in our data centers. We have ways through our tools to mitigate this by either killing the machine remotely, or ensuring that we prune that server’s power by killing it at an infrastructure level. I won’t go into the details here, but we believe efficiency is the high order bit. Do we potentially strand power in this scenario? Perhaps. But as mentioned in the article, if the failure rate is too high, or the economics of the stranding begin to impact the overall performance of the facility, we can always swap the container out with a new one and instantly regain that power. We can do this significantly more easily than a traditional data center could because I don’t have to move servers or racks of equipment around in the data center(i.e. more flexible). One thing to keep in mind is that all of our data center professionals are measured by the overall uptime of their facility, the overall utilization of the facility (as measured by power), and the overall efficiency of their facility (again as measured by power). There is no data center manager in my organization who wants to be viewed as lacking in these areas and they give these areas intense scrutiny. Why? When your annual commitments are tied to these metrics, you tend to pay attention to them.

The last hurdle here revolves around the life expectancy of a server and technology refresh change rates and somehow the price of diesel and green-ness.

"Intel is trying to get more and more power efficient with their chips," Biggs said. "And we’ll be switching to solid-state drives for servers in a couple of years. That’s going to change the power paradigm altogether." But replacing a container after a year or two when a fraction of the servers are actually broken "doesn’t seem to be a real green approach, when diesel costs $3.70 a gallon," Svenkeson said.

Clear as mud to me. I am pretty sure the "price of diesel" in getting the containers to me is included in the price of the containers. I don’t see a separate diesel charge. In fact, I would argue that "shipping around 2000 servers individually" would ultimately be less green or (at least in travel costs alone) a push. In fact, if we dwell a moment longer on the "green-ness" factor, there is something to be said for the container in that the box it arrives in is the box I connect to my infrastructure. What happens to all the foam product and cardboard with 2000 individual servers? Regardless, we recycle all of our servers. We don’t just "throw them away".On the technology refresh side of the hurdle, I will put on my business hat for a second. Frankly, I don’t know too many people who depreciate server equipment less than three years. Those who do, typically depreciate over one year. But having given talks at Uptime and AFCOM in the last month the comment lament across the industry was that people were keeping servers (albeit power inefficient servers) well passed their useful life because they were "free". Technology refresh IS a real factor for us, and if anything this approach allows us to adopt new technologies faster. I get to upgrade a whole container’s worth of equipment to the best performance and highest efficiency when I do refresh and best of all there is minimal "labor" to accomplish it. I would also like to point out that containers are not the only technology direction we have. We solve the problems with the best solution. Containers are just one tool in our tool belt. In my personal experience, the Data Center industry often falls prey to the old adage of “if your only tool is a hammer then every problem is a nail syndrome.”

Challenge 4: Containers are temporary, not a long term solution.

Well I still won’t talk about who is in the running for our container builds, but I will talk to the challenges put forth here. Please keep in mind that Microsoft is not a traditional "hoster". We are an end user. We control all aspects of construction, server deployments and applications that go into our facilities. Hosting companies do not. This section challenges that while we are in a growth mode now, it won’t last forever, therefore making it temporary. The main point that everyone seems to overlook is the container is a scale unit for us. Not a technology solution for incremental capacity, or providing capacity necessarily in remote regions. If I deploy 10 containers in a data center, and each container holds 2000 servers, that’s 20,000 servers. When those servers are end of life, I remove 10 containers and replace them with 10 more. Maybe those new models have 3000 servers per container due to continuing energy efficiency gains. What’s the alternative? How people intensive do you think un-racking 20000 servers would be followed by racking 20000 more? Bottom line here is that containers are our scale unit, not an end technology solution. It’s a very important distinction that seems lost in multiple conversations. Hosting Companies don’t own the gear inside them, users do. It’s unlikely they will ever experience this kind of challenge or need. The rest of my points are accurately reflected in the article.

Challenge 5: Containers don’t make a data center Greener

This section has nothing to do with containers. This has to do with facility design. While containers may be able to take advantage of the various cooling mechanisms available in the facility the statement is effectively correct that "containers" don’t make a data center greener. There are some minor aspects of "greener" that I mentioned previously around shipping materials, etc, but the real "green data center" is in the overall energy use efficiency of the building.

I was frankly shocked at some of the statements in this section:

An airside economizer, explained Svenkeson, is a fancy term for "cutting a hole in the wall and putting in a big fan to suck in the cold air." Ninety percent more efficient than air conditioning, airside economizers sound like a miracle of Mother Nature, right? Except that they aren’t. For one, they don’t work — or work well, anyway — during the winter, when air temperature is below freezing. Letting that cold, dry air simply blow in would immediately lead to a huge buildup of static electricity, which is lethal to servers, Svenkeson said.

Say what? Airside economization is a bit more than that. I am fairly certain that they do work and there are working examples across the planet. Do you need to have a facility-level understanding of when to use and when not to use them? Sure. Regardless all the challenges listed here can be easily overcome. Site selection also plays a big role. Our site selection and localization of design decides which packages we deploy. To some degree, I feel this whole argument falls into another one of the religious wars on-going in the data center industry. AC vs. DC, liquid cooled vs. air cooled, etc. Is water-side economization effective? Yes. Is it energy efficient? No. Not at least when compared to air economization in a location tailor made for it. If you can get away with cooling from the outside and you don’t have to chill any water (which takes energy) then inherently it’s more efficient in its use of energy. Look, the fact of the matter is we have both horses in the race. It’s about being pragmatic and intelligent about when and where to use which technology.

Some other interesting bits for me to comment on:

Even with cutting-edge cooling systems, it still takes a watt of electricity to a cool a server for every watt spent to power it, estimated Svenkeson. "It’s quite astonishing the amount of energy you need," Svenkeson said. Or as Emcor’s Baker put it, "With every 19-inch rack, you’re running something like 40,000 watts. How hot is that? Go and turn your oven on."

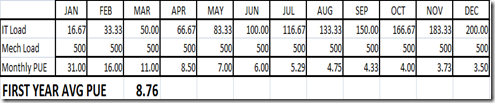

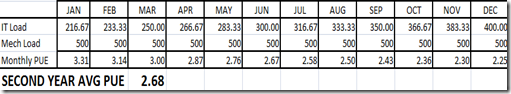

I would strongly suggest a quick research into the data that Green Grid and Uptime have on this subject. Worldwide PUE metrics (or DCiE if you like efficiency numbers better) would show significant variation in the one for one metric. Some facilities reach a PUE of 1.2 or 80% efficient at certain times of the year or in certain locations. Additionally the comment that every 19inch rack draws 40kw is outright wrong. Worldwide averages show that racks are somewhere between 4kw and 6kw. In special circumstances, densities approach this number, but as an average number it is fantastically high.

But with Microsoft building three electrical substations on-site sucking down a total of 198 megawatts, or enough to power almost 200,000 homes, green becomes a relative term, others say. "People talk about making data centers green. There’s nothing green about them. They drink electricity and belch heat," Biggs said. "Doing this in pods is not going to turn this into a miracle."

I won’t publicly comment on the specific size of the substation, but would kindly point someone interested in the subject to substation design best practices and sizing. How you design and accommodate a substation for things like maintenance, configuration and much more is an interesting topic in itself. I won’t argue that the facility isn’t large by any standard; I’m just saying there is complexity one needs to look into there. Yes, data centers consume energy, being "green" assumes you are doing everything you can to ensure every last watt is being used for some useful product of work. That’s our mission.

Challenge 6: Containers are a programmers approach to a mechanical engineer’s problem.

As I mentioned before, a host of professional engineers that work for me just sat up and coughed. I especially liked:

"I think IT guys look at how much faster we can move data and think this can also happen in the real world of electromechanics," Baker said. Another is that techies, unfamiliar with and perhaps even a little afraid of electricity and cooling issues, want something that will make those factors easier to control, or if possible a nonproblem. Containers seem to offer that. "These guys understand computing, of course, as well as communications," Svenkeson said. "But they just don’t seem to be able to maintain a staff that is competent in electrical and mechanical infrastructure. They don’t know how that stuff works."

I can assure you that outside of my metrics and reporting tool developers, I have absolutely no software developers working for me. I own IT and facilities operations. We understand the problems, we understand the physics, we understand quite a bit. Our staff has expertise with backgrounds as far ranging as running facilities on nuclear submarines to facilities systems for space going systems. We have more than a bit of expertise here. With regards to the comment that we are unable to maintain a staff that is competent, the folks responsible for managing the facility have had a zero percent attrition rate over the last four years. I would easily put my team up against anyone in the industry.

I get quite touchy when people start talking negatively about my team and their skill-sets, especially when they make blind assumptions. The fact of the matter is that due to the increasing visibility around data centers the IT and the Facilities sides of the house better start working together to solve the larger challenges in this space. I see it and hear it at every industry event. The us vs. them between IT and facilities; neither realizing that this approach spells doom for them both. It’s about time somebody challenged something in this industry. We have already seen that left to its own devices technological advancement in data centers has by and large stood still for the last two decades. As Einstein said, "We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them."

Ultimately, containers are but the first step in a journey which we intend to shake the industry up with. If the thought process around containers scares you then, the innovations, technology advances and challenges currently in various states of thought, pilot and implementation will be downright terrifying. I guess in short, you should prepare for a vigorous stirring of the anthill.